Looking Out For Troubled

Children

Buoyed by research indicating vision

problems as the root of some educational and behavioral problems, a nationwide

initiative forms

By Susan P. Tarrant

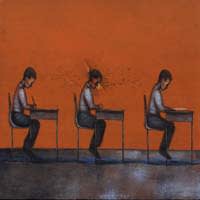

Illustrations by Jon Klause

Little Johnny can read, but he�s still not doing well in school. He seems to struggle with his homework. He refuses to read aloud in class. He gets frustrated and angry easily. And, sometimes, Little Johnny takes that frustration out on his classmates, by hitting or kicking. Other times he�s withdrawn and sullen.

There could be many causes of Little Johnny�s behavior, to be sure. Any child development expert worth his salt would be quick to come up with a list. However, until recently, that list might have omitted a possible vision problem.

Buoyed by convincing research by child development experts and Virginia-based optometrist Joel Zaba, O.D., a nationwide movement is underway to carefully examine children for near-point vision, eye motility, and teaming. The hope is to catch such problems before they manifest themselves into other problems.

It�s a hope embraced by the American Optometric Association (AOA), Vision Council of America (VCA), the VCA�s Better Vision Institute, Prevent Blindness America (PBA), and a host of other education and vision organizations. The goal is to pass legislation in every state that mandates a full vision exam�by an O.D. or ophthalmologist�for all children prior to entering school, and periodically thereafter.

"Vision is a tool for school children, just like paper and pencils," says Zaba, who has spent most of his 20 years in practice focusing on children�s vision and the issues associated with it. "Children should not be sent to school without the proper tools�including good vision."

Zaba emphasizes that, of course, simply treating visual problems will not solve all the problems of at-risk students. He says, however, that visual problems should be considered one of the roots of a problem.

"No one profession has all the answers. But all the professions working together can help the kids," Zaba tells Eyecare Business. "Every child is like a puzzle and you have to put the pieces together. The part that has been missing often times is the visual piece."

Zaba presented his theory, based on countless studies and years of research with other vision professionals and educational experts, at a conference in April at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education. In it, he presented the following statistics:

- From the National Parent Teacher Association: More than 10 million children suffer from visual problems.

- From PBA: Vision problems affect one in 20 preschoolers and one in four school-age children.

- From the AOA: Vision disorders are a common pediatric problem in the United States, with an estimate of nearly 25 percent of school-age children having vision problems.

The Roots of a Study

His practice began as a children�s practice, and it was there that he started realizing that lifelong vision problems often had their root in the young years, but were undetected.

"The adult visual problems can interfere with the person�s work performance �whether it�s an attorney who takes four hours to read a brief when it should just take an hour or an adult illiterate who decided to drop out of school because he got so frustrated," says Zaba. "These were kids who, 20 years ago, people missed because nobody understood the relationships between vision and learning."

Vision problems, undetected in early years, can also manifest into other behavioral problems, he states.

Research by Zaba and Roger Johnson, Ph.D., of Old Dominion University, indicates that undetected vision problems can possibly lead to low self-esteem, anti-social behavior, poor performance in school, learning disorders, and delinquency.

"It�s definitely not a black and white, cause and effect thing," he says. "What I�m saying is that vision is part of the total picture of looking at the child."

Zaba is by no means alone in his efforts. His research has formed the basis for the Vision Council of America�s (VCA) Children�s Initiative, which is trying to raise the public�s and the profession�s awareness of the importance of early detection of vision problems in children, and to push for mandatory comprehensive visual exams.

Already, there is success. Kentucky made big news this spring when its legislature passed the first law in the counry mandating comprehensive vision exams for children.

And many more states are trying to follow suit. Similar legislation is being considered in California, Connecticut, Wisconsin, Missouri, Ohio, and Massachusetts. New York City Comptroller Alan Hevesi, who is campaigning to be mayor, announced last month that he is supporting the New York City Children�s Vision Coalition�s efforts to get a similar bill introduced in New York.

And that is music to the VCA�s collective ears.

"We�re not anti-screening," says Joseph LaMountain, vice president of strategic communications for VCA. "Screenings can diagnose visual problems. But the problem is that all too often there is no follow-up on the part of the parent or the screener. The loop sometimes doesn�t close.

"If a child is already at an eye doctor�s office getting his mandated comprehensive exam, and the doctor detects a problem, the doctor is going to make sure there is follow-up," he continues. "The loop gets closed."

And, if the experience in Kentucky is any indication, the loop gets closed effectively. According to statistics released by VCA, 45,000 children have already received comprehensive vision exams as a result of the law.

Preliminary data show that 18.7 percent of six-year-olds needed corrective eyewear, while an additional 2.4 percent had strabismus, and 3.6 percent had amblyopia. Those children had previously been screened as part of the required physical exam before entering school.

|

|

Who�s Leading the Cause? |

|

Several states are now passing or considering legislation that would require full vision exams for young children entering their school years. How is your state faring? LEGISLATION PASSED Kentucky LEGISLATION INTRODUCED California |

The challenge, according to Zaba and LaMountain, is convincing the state legislatures that no state funding is required to support the mandate. The funding exists in the form of private insurance, Medicaid, social service programs, and�if needed�O.D.s who would do the exam pro bono, as happened in Kentucky in one or two cases.

Get Involved

"There are 49 states that have not passed legislation," says LaMountain. "So there is plenty of opportunities for eyecare professionals to become involved in their states."

VCA has created a manual that not only outlines the data, research, and basis of the Children�s Vision Initiatives, but includes tips on how to raise awareness. It has sample press releases to send to local media, tips for getting involved in the schools, and simply raising awareness in your community.

For more information on children�s vision issues, and the VCA Initiatives, visit www.visionsite.org\profes\onlinerelease.html.

The professional and personal rewards, according to Zaba, are plentiful. "You�re affecting the life of the child. Those are the types of things that really give extra meaning to what you do, and is really what the profession is all about."